Causes of Calf Strain

A calf strain generally occurs as a result of excessive tensile overload force, such as a sudden running volume or intensity increase (e.g. heavy hill running without adaptation). Contributing biomechanical risk factors also include weak or restricted glutes and hips, quads, and/or poor ankle mobility.

A. Volume or Intensity Increase

Tissue takes time to adapt and get stronger, so if you persistently push it beyond its limits of recovery then you will get calf discomfort or injury. This not only occurs from increasing intensity too quickly in training, but also from doing too much too soon after having taken time off, such as for travel, injury, or sickness, during which the tissue has weakened from inactivity.

QUESTIONS:

- Did I recently change my running program?

- Do I allow adequate rest in my running program?

- Do I participate in other activities that may be overloading the calf?

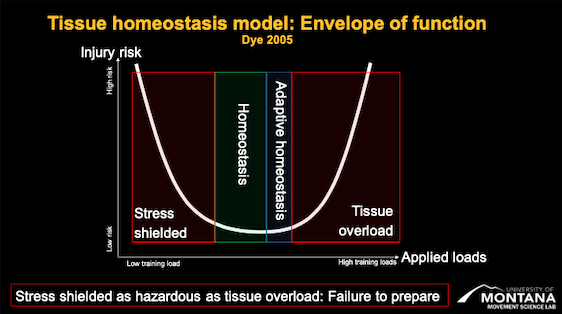

This “U” shape graph indicates Injury Risk (Vertical/ Y-Axis) and Load (Horizontal/ X-Axis). If you don’t train much (low load), your risk of injury is high due to the low resilience of the tissue. If you are training a lot, your risk for injury is also high due to potential overload. The middle zone provides the lowest risk of injury. To increase load capacity, you will have to move toward the higher load zone, but the key is to do so progressively to allow the tissue to adapt. This will be addressed further in the conditioning and training portions of ARC Running.

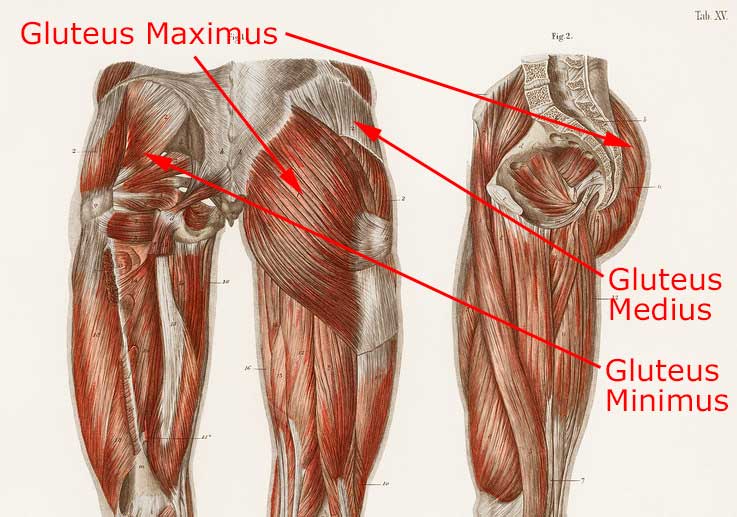

B. Glutes & Hips

With every step, and thereby every load on our legs, the glutes and hips are active in preventing the knee from caving inwards. If the knee collapses too much or there is a delay in firing of the glute, then there are more forces and strain on the calf to absorb increased pronation (i.e. foot rolling in).

ASSESSMENT TESTS:

Side Planks

If you can hold for 90 seconds, you are good. Less than 90 seconds indicates weakness in the side of the hip, as does trunk rotation or dipping hips that break your initial position.

Instructions: Elbows aligned with shoulders, come up on your side. Keep your body straight throughout the duration of the test. The test is complete when your hips begin to drop, you begin to rotate, or you get too tired to continue.

Single Leg Glute Bridge

If you can hold for 60 seconds, you are good. Less than 60 seconds indicates weakness in the glutes, as does an inability to maintain a level body/ hip height and/or experiencing trunk rotation while trying to maintain the position.

Instructions: On your back, bring your hips up with arms across your chest. Hold your body level throughout the duration of the test. The test is complete when your hips begin to drop, you begin to rotate, or you get too tired to continue.

Single Leg Squat

Can you squat without the knee wobbling or caving inward? Excessive knee movement or inability to reach a 90-degree squat indicates hip/leg weakness or motor control deficits.

Instructions: On one leg, begin to squat down by bringing your hips back and then bending your knee. Look to see if the knee is aligned with the middle of your foot throughout the duration of the movement.

Running Assessment

When you run, do your legs run parallel or cross a midline? If your leg crosses your body excessively (across midline), this can indicate that more pressure is being placed on your knees from your running form.

Instructions: Notice yourself by using a track. Do your feet cross the midline when you run? (A friend may be able to see this better than you.)

Side Planks

If you can hold for 90 seconds, you are good. Less than 90 seconds indicates weakness in the side of the hip, as does trunk rotation or dipping hips that break your initial position.

Instructions: Elbows aligned with shoulders, come up on your side. Keep your body straight throughout the duration of the test. The test is complete when your hips begin to drop, you begin to rotate, or you get too tired to continue.

Single Leg Glute Bridge

If you can hold for 60 seconds, you are good. Less than 60 seconds indicates weakness in the glutes, as does an inability to maintain a level body/ hip height and/or experiencing trunk rotation while trying to maintain the position.

Instructions: On your back, bring your hips up with arms across your chest. Hold your body level throughout the duration of the test. The test is complete when your hips begin to drop, you begin to rotate, or you get too tired to continue.

Single Leg Squat

Can you squat without the knee wobbling or caving inward? Excessive knee movement or inability to reach a 90-degree squat indicates hip/leg weakness or motor control deficits.

Instructions: On one leg, begin to squat down by bringing your hips back and then bending your knee. Look to see if the knee is aligned with the middle of your foot throughout the duration of the movement.

Running Assessment

When you run, do your legs run parallel or cross a midline? If your leg crosses your body excessively (across midline), this can indicate that more pressure is being placed on your knees from your running form.

Instructions: Notice yourself by using a track. Do your feet cross the midline when you run? (A friend may be able to see this better than you.)

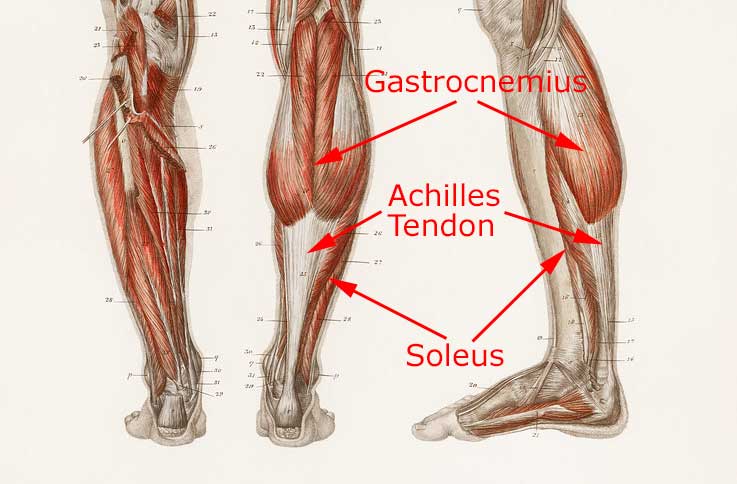

C. Calf Strength

Weakness in the calf is a significant factor that contributes to a calf strain. The calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) absorb significant forces during running. A strong calf reduces the risk of calf strain by increasing its resilience to external loads.

ASSESSMENT TESTS:

Ideal is 25 reps on one leg:

Gastrocnemius: Standing on a step with heels off the edge, bring yourself up and down on your toes while keeping your knees straight. Go up and down to the same level each time. If you start to fatigue or can’t get as high, then stop the test.

Soleus: Standing on a step with your heel off the edge and your knee bent, bring yourself up and down on your toes, keeping your knee bent the whole time. Go up and down to the same level each time. If you start to fatigue or can’t get as high, then stop the test.

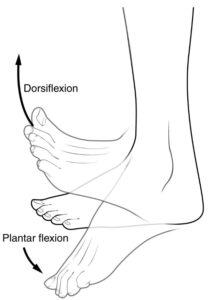

D. Ankle Mobility

Ankle dorsiflexion is the ability of the ankle to flex (bend up toward the shin), while plantar flexion is its ability to extend (bend backwards away from the shin). Decreased dorsiflexion, most evident with foot strike during running, may cause you to compensate with additional pronation and thereby increase the strain on your calf.

ASSESSMENT TEST:

Can you dorsiflex your ankle 20 degrees? Test this by kneeling forward, seeing how far your knee comes over your toes. It should be at least 3 inches over your toes.

E. Other Risk Factors

- Prior Injury: Not having fully recovered and/or strengthened weakened area(s).

- Training Dynamics: Different running surfaces, speeds, and distances.

- Sleep, Nutrition, and General Recovery: If you don’t eat well, your tissues don’t have the fuel needed to restore muscle.

- Advanced Age

Still Need Help?

You are welcome to meet virtually with our PT for additional feedback and assessment. Otherwise, continue to the next step to learn how best to manage the pain from your injury.